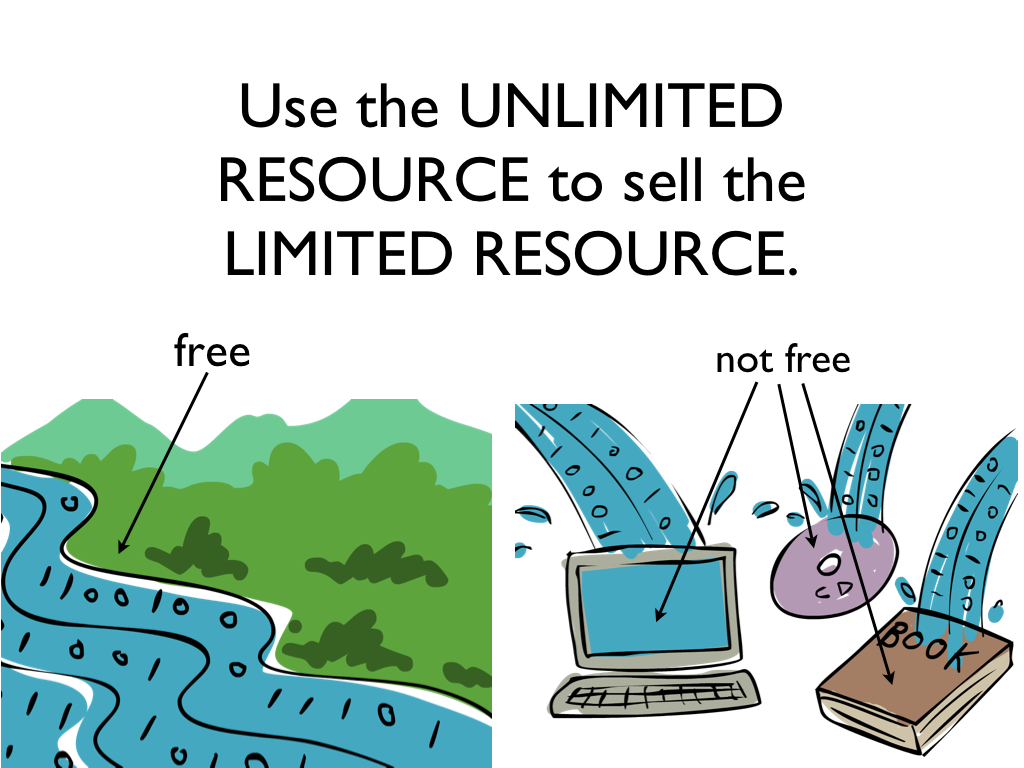

Content is an unlimited resource. People can now make perfect copies of digital content for free. That’s why they expect content to be free — because it is in fact free. That is GOOD.

Think of “content” — culture — as water. Where water flows, life flourishes.

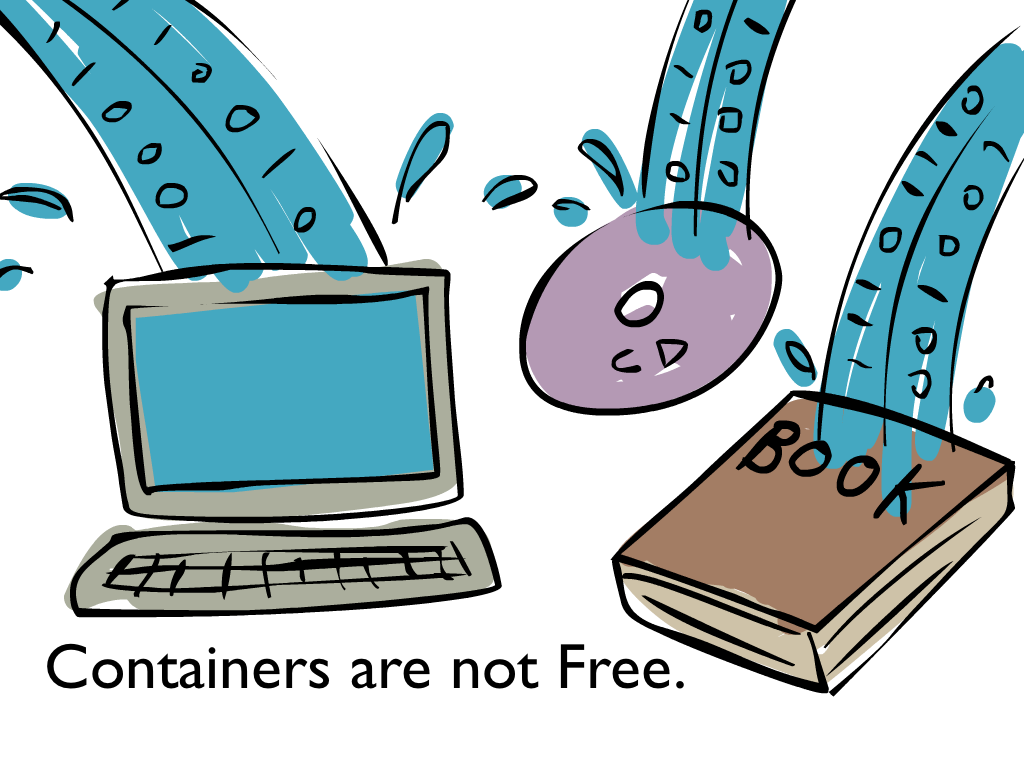

Containers — objects like books, DVDs, hard drives, apparel, action figures, and prints — are not free. They are a limited resource. No one expects these objects to be free, and people voluntarily pay good money for them.

Think of “containers” — books, discs, hard drives — as jugs and vessels. These containers add utility to and increase the value of the water. If you can get water for free in the public river, great — that doesn’t reduce the value of vessels. Quite the contrary: when rivers flow, the utility and value of water vessels increases.

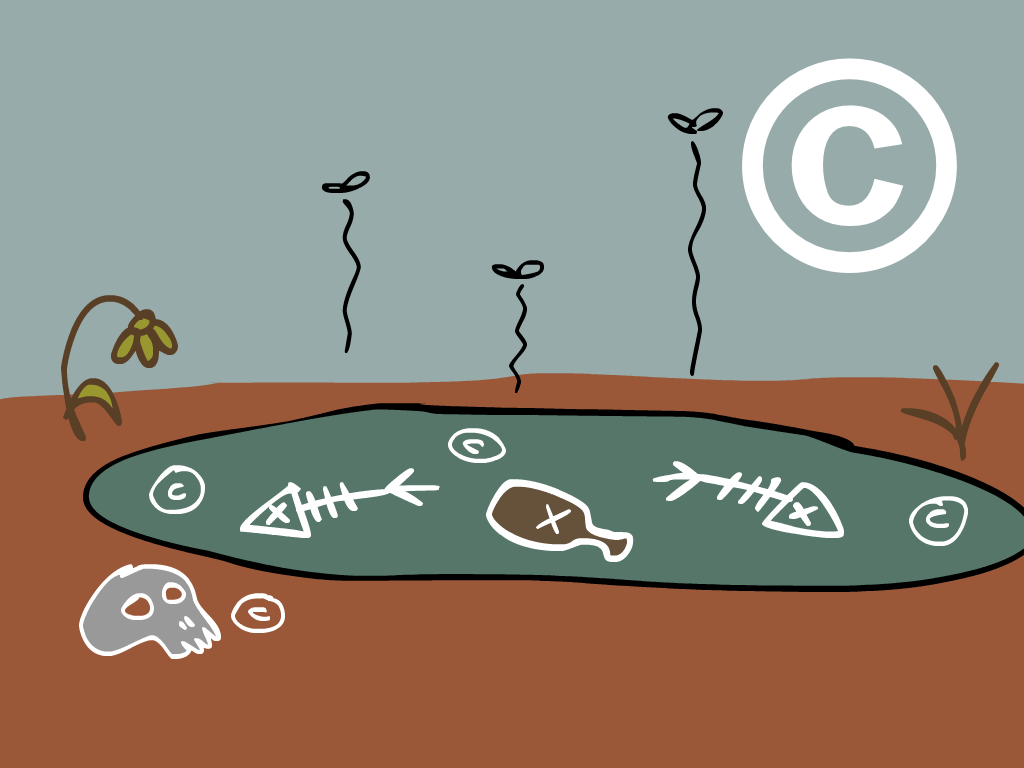

Continuing this metaphor: copyright monopolies are an attempt to dam up and control all the rivers, reducing them to a trickle. When Big Media succeeds locking up culture, it’s like in closing off water: they get a stagnant pool that turns to poison. Fish die and mosquitoes swarm, because the water has no source to flow from nor destination to flow to.

(That’s how we get things like this.)

(That’s how we get things like this.)

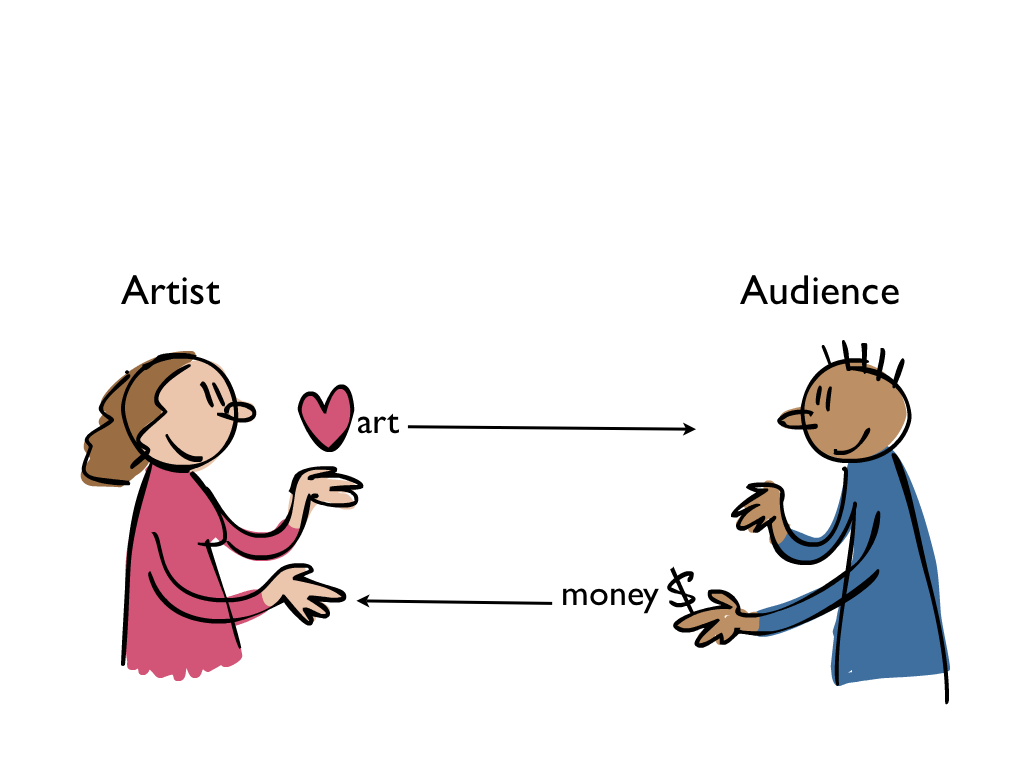

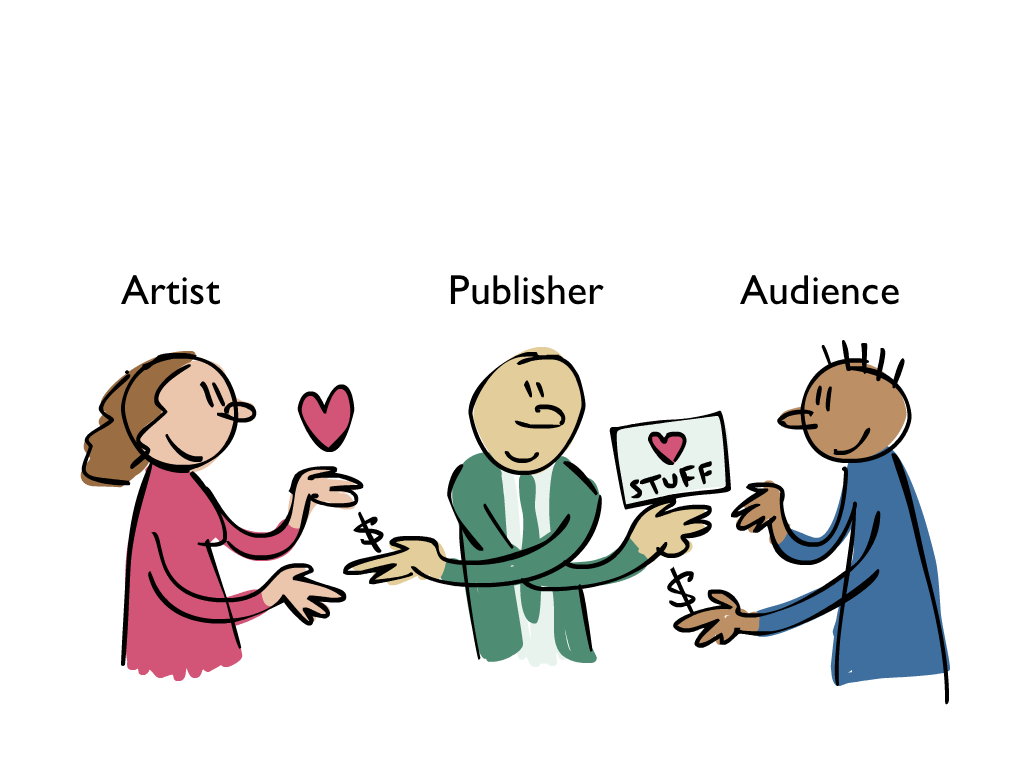

Artists don’t “own” culture, but we do own our names (attribution). Any artist who has enjoyed a community of fans knows how the power in their name is generously granted by audiences. Our audiences want us to thrive. They want their money and support to reach us.

Therefore an artist’s cooperation with a merchandiser is valuable. A signed book is worth more than an unsigned one. Merchandisers who cooperate with artists — share revenue with them — get the blessing of both artist and audience and can sell more objects for more money.

Under the Creative Commons Share Alike license, Sita Sings the Blues-containing objects can be manufactured and sold by anyone without my permission. But whoever shares revenue with me gets my “creator endorsed mark” or signature, and gets my fans sent to the product (via community word-of-mouth and my web site).

Competing products can nonetheless be sold without my endorsement. If they’re cheaper, of better quality, or more accessible, they might sell better than my endorsed products. Why shouldn’t they? Competition can be good. All the more incentive for any business I partner with to make their products high quality, reasonably priced and easily available. There’s no incentive to compete with a good product; if there’s a good affordable Sita Sings the Blues coffee table book or graphic novel, why should anyone bother publishing another? If they do, the competing book must have some important quality lacking in the first. If that competitor’s quality differential is so high it’s worth more than my endorsement, then good for them for doing something right.

Remember:

Free Enterprise is Free Culture too.

Common Questions about Free Content:

Q. Why make a book when you can get the content free on the Internet?

A. Because there are limits to the Internet. You can’t touch it or smell it. Images are restricted to screen quality and may cause eyestrain.

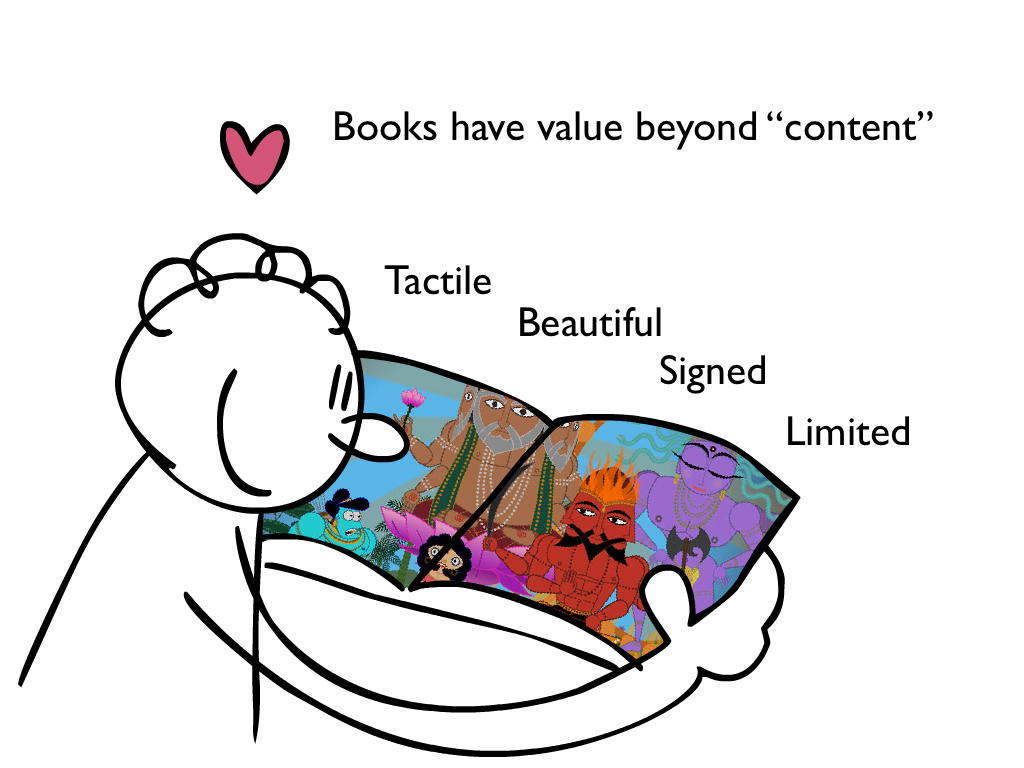

Books have value as objects beyond the intellectual wealth they embody. They are portable, tactile, and invulnerable to power outages. Art books can have even more valuable attributes: glossy coatings, embossing, reflective and matte inks, paper textures, super-high resolutions. Books can be beautiful objects in their own right. Signed books are works of art. Books can have value as collector’s items, because they are LIMITED.

Audiences seek a connection with creators. Even if the content is free, many fans desire a physical token of the work. They also want to support the artist. Merchandise — objects, like books, DVDs, apparel — acts as a medium to conduct these artist-audience transactions.

Q. Why make it free on the internet if it’s available as a book (or DVD, CD, etc.)?

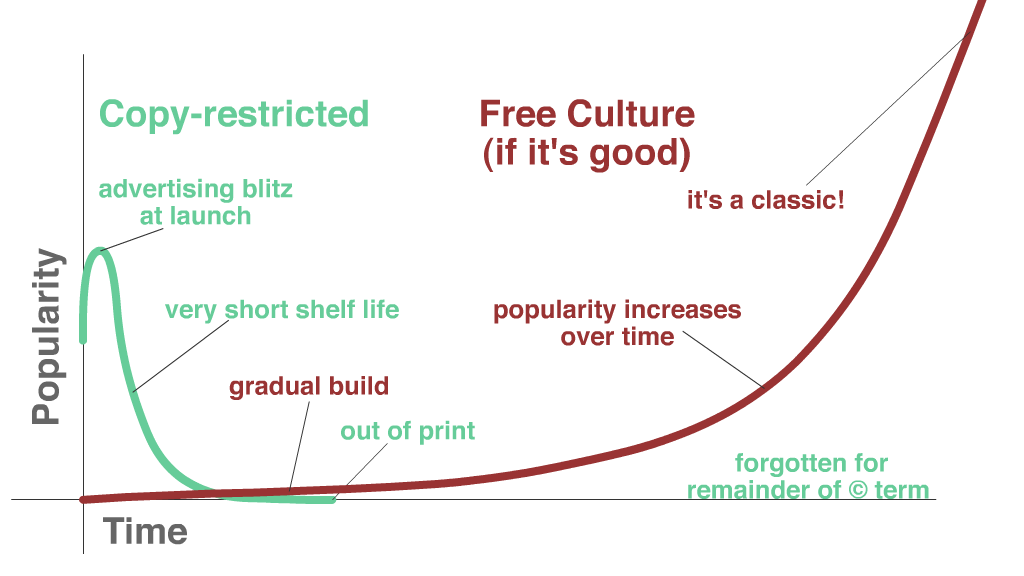

A. Because if it’s free, it can spread. If it’s good, the audience will quote it, cite it, share it, review it, and promote it. Free accomplishes everything advertising does, except it’s good not evil, free not controlled, voluntarily shared not forced down throats. Instead of spending vast sums on crappy advertising to sell “content” you’ve locked up, just free the content and let it advertise itself. Use the unlimited resource to sell the limited resource.

Q. But even with the internet, I still have to advertise!

A. Maybe. Depends on what your content and how much time you have. If what you have is good, just give it time. “Viral” growth is exponential, but it can take a while. Or you can use advertising to artificially direct audience attention to something they wouldn’t care about otherwise. If the work is not good, interest will drop off when advertising does.

That’s our vision of Free. It’s not communism. It’s not capitalism as we know it. It’s definitely not monopolies. It is Free Culture, and Free Enterprise.

….but how dare you pour water on that sweet, innocent computer? >:o

So the DVD case manufacturer should get paid, but not the filmmaker?

As a filmmaker who has spent the last 5 years shooting, editing, and now distributing my film (at most of the same venues as you BTW) am I simply to give my work away for free, simply to get my name noticed?

I can see it now – “hey power company, I can’t pay my bill, but do you know who I am?” Yeah, that will go far.

The reality is that you ignored many people who told you not to use music that you did not have the rights to. Now you can’t hop on the distribution train (which you admit you tried to do), and now that nobody wants to touch your radioactive product you are giving it away and trying to make it sound as if filmmakers who actually create art and actually (gasp) make money at it are douchebags?

Give your head a shake lady. You messed up and ruined what could have been an awesome money making opportunity. Too bad. Move along to your next project and admit you screwed up.

It’s always questionable whether we should even leave this sort of comment on the site or not, sigh…

First, Nina Paley has never said anything to insult her fellow filmmakers, whether they agree with her positions on freedom of information or not. I don’t know where you got that “douchebag” language from, but it certainly wasn’t Nina. Nor has she ever been opposed to anyone making money, and in fact is making some herself — more than she would have under a standard exclusive distribution arrangement (a fact you may have been unaware of).

You speak of these “rights” as though they’re natural, unchangeable things, instead of government-granted monopolies whose exact terms are a matter of policy. Of course, they are the latter: that’s why these monopoly rights weren’t invented until there was a centralized distribution mechanism (the printing press) to benefit from them.

Regarding her so-called “radioactive” product: Nina is now struggling to keep up with all the emails from distributors who want to distribute her film under non-exclusive terms, and who want her endorsement or involvement. Again, you might not have known this; on the other hand, you could stop for a moment and wonder who exactly is setting up all those screenings of the film that are publicly listed, if the film is so radioactive that no one wants to touch it.

Finally, if there’s money to be made selling DVDs, then the artist is just as free to sell them as anyone else, and is in the best position to do so. That’s exactly what Nina is doing. You’re welcome to do it too.

Lots of people work hard at what they do. I used to work hard in a bagel shop, and the owner there worked three times as hard as I did. Yet no one has ever suggested that he should be “protected” from competition by being given a government monopoly on the recipe for bagels, or a monopoly on selling bagels on that street. I’m glad you finished your film, and wish you luck with it, but your hard work is not a justification for interfering with the rights of people to use their computers and networks for the purposes for which they were designed: to share information and culture with each other. Since when does hard work justify censorship and monopoly? In other fields it doesn’t, and it shouldn’t in this one either.

-Karl Fogel

*Sigh* – you just cut your own argument off at the knees. If distributors are stumbling over each other to get the rights to her film, they are obviously willing to pay the required licensing fees. Thus the system isn’t broken.

Re: bagels, nobody is stopping somebody from making other films. That’s fair competition. Stealing your bagels and reselling them isn’t competition – it’s theft.

Get a clue.

Wish I’d known that before I paid my sound guys, camera people, video and audio editors, lighting crew, caterers, airlines, rental houses, and location permits.

I would have saved myself a lot of money.

Good lord, you guys are delusional.

No matter how much you pay anyone, including yourself, you can’t make your stuff non-copyable. Face it: you live in a networked world. You’re fooling yourself if you think there’s such a thing as “controlled release” anymore. Our argument is simply that this is okay: freedom for everyone to share is more important than the narrowly-focused benefits of granting monopolies on distribution — monopolies that come with not-so-narrowly-focused costs, such as that they criminalize normal human activities like sharing.

Your argument is nonsensical. Because someone can break DRM then that makes it ok? I can pick a lock to my neighbor’s house does that give me the right to take his items because I can? No.

As a filmmaker I absolutely SHOULD have the “monopoly” to decide who can get access to my art, and where it ends up. Just because people can pirate material doesn’t mean they should.

You confuse SHARING, which is where the artist willingly allows the art to be shared (as I have done with benefit screenings for charities), with STEALING – the unauthorized copying of my material, which deprives me of my rightful compensation.

STEALING does not equal SHARING.

Hi!

I allowed myself to translate “Understanding Free Content” into Polish and put it here:

http://luckyluke7777777.blogspot.com/2009/06/tumaczenie-nina-paley-zrozumiec-wolna.html

Thanks! Keep up the good work!

Luke7777777

_______

Luke7777777.blogspot.com

http://luke7777777.blogspot.com/

CATHOLICISM > LIBERTARIANISM > INFOANARCHY

LuckyLuke7777777.blogspot.com

http://luckyluke7777777.blogspot.com/

CULTURE, MEDIA & STUFF

I don’t know how to say Thank You in Polish, but Thank You!

I think it will be inevitable that understandings of what exactly free culture is and how to use it to make money will have to build slowly.

Thanks Nina for a real “ideas in action” demonstration of free culture at work!

We have blogged about it on our open media site http://pool.org.au

http://www.pool.org.au/blog/pool_team/artists_earn_from_free_culture

Cheerio John

I really like your point about free enabling a far more reasoned, fair awareness of what you’re offering, than traditional advertising.

I’ve struggled with advertising for a long time; artificially trying to induce want for something is really not a great thing, psychologically, or more broadly as a society.

The free model, while still imperfect, seems like a great step forward from advertising. I like this a good deal. I’ve recognised this for a long time in free software, but for some reason never made the connection to other copyable work.

Thanks!

Nina Paley has argued that the audience contributes to the value of a work of art. I made a similar argument in a book about music. First we have Nina’s statement and then we have mine.

1) Nina Paley, from a comment somewhere up there:

“I contributed about 7,800 hours to making Sita. That’s a lot of time, and every hour I put into it made the film more valuable. I conservatively estimate the audience has contributed at least 300,000 hours to Sita, probably a lot more. Every hour they put into the film makes it more valuable. They’ve put a lot more hours into it than I have, and I haven’t paid them a dime. Yet I enjoy attribution for the film, and all this value accrues to me! Sweet.

“If you don’t believe that the value comes from the audience, and is instead inherent to the work itself, then by all means please keep your work safely hidden, and don’t publish it.”

2) Me, from the last chapter of my book, Beethoven’s Anvil, where I talk about Louis Armstrong and a particular phrase he liked to quote; in particular, note the last sentence:

“The greatness of an individual musician such as Armstrong is a function, both of his power to forge compelling performances from the “raw” memes and of the existence of that meme pool. While Armstrong may have been ahead of his fellows, he couldn’t have been very far ahead of them, otherwise they could not have performed together. Beyond this, without a large population of music-lovers familiar with the same meme pool, Armstrong’s recordings would have had little effect. By the time he went to Chicago, a large population had been listening and dancing to rags and blues, show tunes, fox trots and Charlestons and marches, all with a hot pulse and raggy rhythms. Armstrong’s improvisations gave them a new wild pleasure, and their collective joy made him great.”

— Bill Benzon

“While Armstrong may have been ahead of his fellows, he couldn’t have been very far ahead of them, otherwise they could not have performed together.”

Nicely put, Bill.

I am not sure that what you advocate would work well enough – but I know the current system doesn’t work very well either! In any case, it’s important to get people to question the purpose and effectiveness of copyright (and patents), and look for alternatives. The current corporate takeover (people need to re-examine the purpose and effectiveness of corporate charters too) has to my mind clearly gone too far, and there isn’t enough “push-back”. Your advocacy is important push-back, getting people to question the assumed legitimacy of current copyright practices (or even copyright at all).

It’s important that people understand the copyright is not an individual right like freedom of speech, but (in the US anyway) a limited special privilege granting the power of the state (enforcing monopoly) for the purpose of serving the best interests of the population – by fostering creativity and distribution of creative works. Copyright advocates should have the burden of proof in maintaining, much less expanding, this special treatment – needing to demonstrate from time to time that the monopoly should be continued because it IS indeed fostering the results that justify it, better than other methods. Your alternate viewpoints should be considered in the discussion.

But of course copyright legislation is about who has money for lobbyists and campaign donations, not about a balanced discussion of how best to foster creativity. For now, the most we can hope for in the short run is to puncture the smug certainty that copyright is obviously correct – create some cracks in the hermetic seals around the status quo. But all big cracks start as small ones.

Kind regards, Zeph

I hate to ask this. But who is going to sell a movie on a hard drive? I mean maybe a SD Card or something.P.s. Love the movie.

“Digital technology is the universal solvent of intellectual property rights.” -Tom Parmenter

Since I’m supposed to buy multiple copies in your world, am I disallowed remembering, describing or re-enacting scense without paying you? If my hard drive of memories is subject to policing, why not my head?

The culture, or body of water, represents for the most part the oral tradition. Stories and songs passed down from memory, freely available for anyone to listen and recall whenever needed. The best actor/storyteller/singer/dancer is container and conduit for the content. The best performers inspire all before them, and create new performers with their own interpretations to suit their own times as the culture changes over time.

The containers are still limited resources, especially if they are people. Only a few people have the opportunity to see one performer’s work over their lifetimes. The ability to store performances by writing (even dance movements can be rapidly described in notation) them down, allowing future performances to approximate great works after the originators are no longer able to repeat themselves.

[EDIT: link removed]

I would like to discuss this in a more broad perspective. The freebie-loving nature of humans makes free content inevitable. Let me give you a few examples, What would make questioncopyright.org skyrocket in traffic for a single post? Simply, free tools, freebies or a free source of services rendered in the post for readers to benefit from. If one replaces such post with an advertisement or a press release type of posts, most likely there will only be one type of people interested: “potential customers”. And trust me they are not as many as free content seekers.

Another example is PDF books. A research has proven that most of internet users would rather read a free book if it was claimed to be sold elsewhere (the get-this-for-free-for-limited-time-only marketing style) rather than a direct free-to-download ebook. (This did not prevent Amazon from sitting on gazillions of dollars out of selling books though, wink wink).

Last example is that most web searcher try to find cracked content and software rather than search for the direct sales page for their target product. There will always be one site for the product, and thousands of cracking sites for the exact same product. Why? You get the idea.

Great article BTW.

Medo Joe.

Trading Systems.

“But who is going to sell a movie on a hard drive?”

Many digital films (for theaters) are already distributed on hard drives. A digital film longer than 90 minutes can take up over 170 gigabytes of space! I don’t think that can fit on an SD card.

This says it perfectly. I think that having free information online is wonderful because it eliminates a lot of physical pollution in the sense of cases and so forth. It also makes it so that you can get exactly what you want or research something that you think you may need in your life.

My father wrote a book Culture vs. Copyright, where he examines free culture ideas in detail. There is in-depth analysis of both how culture itself works, as well as how free-culture economy supports authors, their audience, as well as intermediaries. The conclusions are very similar yo ones posted in this article.

The book is written in mixed ganre, and is fun to read. It’s posted online, and is distributed (obviously) under license which allows commercial and non-commercial re-distribution.

I realize I’m late in joining this conversation, but the subject continues to be an issue and I really do want to understand your reasoning.

It appears that you are making the argument that only physical objects have intrinsic value. Are you completely opposed to the idea of “Intellectual” property? Do you believe that if someone produces some sort of work, then makes it available for viewing or listening that it automatically becomes, or should become, part of the public domain?

How are you defining value? Is there no distinction to be made between monetary, cultural or utilitarian values? Let’s say I dig a ditch. Ten people watch me swing the pick axe and go and tell their friends. A hundred of them come to check out my little trench. Does that add value to the ditch? How? Is it worth more if I sign my name in the dirt or put up a plaque with my name on it?

Containers do not add to the intrinsic value of water. They are simply delivery systems. The power of water is already in the water. It has inherent value independent of your ability to access it. And no one had to labor to cause it to exist. And like water, content is not “in fact free”. It’s costing whoever is upstream working to make that content something to make it. When I pay my water bill each month, I’m paying not only for the delivery infrastructure, but for the water as well…two separate things, each with a value and an attending cost.

Why do you see culture and content as synonymous? How are you defining culture? Which culture are you referring to? In what way might your film contribute to the culture of some remote tribe of bush people in the Rain Forrest?

Unlike most of the other commenter’s, I’m not a film maker. I’m a songwriter & music producer. And I publish my own works. I am hardly “Big Media”. I am one solitary person whose copyrights have been a valuable resource. I don’t expect to be paid simply because I put in XXX amount of hours to complete a project, but if someone likes the end result enough to want to possess a copy of it, in whatever form that might take, why shouldn’t I be allowed to put a price tag on it? They are free to decide whether or not they want it enough to pay what I’m asking, just like they would a bucket, a chair or a can of tennis balls. And how would I sign a download?

Music theory is “information”. Recording techniques are “information”. The works I create are not. They are the result of my having devoted my time, energy, money, and effort, all of which are finite resources, to see a thing through to completion. That makes them a product. Just because my work can be digitized and infinitely reproduced without depriving me of the original rendering doesn’t relegate that work to the realm of ideas or information.

I’m having an especially difficult time wrapping my head around the idea that an audience should be paid for…well, being an audience. If an artist is doing their job successfully, the audience is compensated in any number of ways. They might be inspired, excited, moved, become better informed, gain new insights or points of view, or just simply be entertained for a little while. Each of those results has value. That’s what I get in return for watching a film, attending a reading or exhibition, or listening to music.

Hi Anon. Of course, I can’t speak for Nina, but I hope I can help you find a better perspective on the subject.

“It appears that you are making the argument that only physical objects have intrinsic value.”

When holding a book and reading what is not on screen, were the valuable things that Nina mentioned physical, or based on what was physical? What makes us value physical objects more than non-physical objects is subjective, as value is determined subjectively.

“A hundred of them come to check out my little trench. Does that add value to the ditch? How? Is it worth more if I sign my name in the dirt or put up a plaque with my name on it?”

Of course not. Value does not get added to a work by people just looking at it. You could make a sideshow involving pineapples and hammers, but if people won’t like it, they won’t see it as valuable. The only way value for your ditch digging can go up is if you are somehow impressing somebody. I would say you must do things in a very unusual way if you got one hundred people to watch you dig a ditch!

“Why do you see culture and content as synonymous?”

I identify with your skepticism here. Both culture and content of these can exist as information, a metaphysical construct. “Content” is what we call things that describe something else, which can include culture. However, culture can also help establish a means to generate content. They may not be synonomous, but they can be interdependent concepts.

“I’m having an especially difficult time wrapping my head around the idea that an audience should be paid for…well, being an audience.”

If an audience takes time out of their lives to promote something seriously (which would involve freely manufacturing something), it isn’t unfair for them to request compensation for their labor. Now, if they were profiting from an artist’s work via plagarism, then we’d have a problem.

“Music theory is “information”. Recording techniques are “information”. The works I create are not.”

Sorry, but yes, your work may very well be information. Products and information have merged, meaning I can now send people movies, comics, games and other things to people as if it were a message (or via a kind of “speech”, if you will). Although you can certainly treat information like a product, that does not necessarily mean it magically loses the properties that also make it information. Now, if you made a big hulkin’ machine, then I would not call that a product-information hybrid.

Information exists as obervable properties in physical arrangements. The properties and their “meaning” are defined by intelligent observers. As far as reality cares, this text is just a bunch of stuff. However, the arrangement of the electrons in this webserver forms all sorts of things to finally end up representing language that you understand, and maybe even value.

If you bust your butt making music, and your music is on your computer, it physically exists as a hardware state. The arrangements are interpreted by us as melody (we tell computers to interpret it that way too!), and we like that stuff. What you have to remember is that your music really is information. Share it! We might want to give you money to make more.

“If someone likes the end result enough to want to possess a copy of it, in whatever form that might take, why shouldn’t I be allowed to put a price tag on it?”

I won’t say you should not. I think you have all the right in the world to ask for compensation. But, in a capitalist economy, trade is free. This means people do not have to pay you. Since it is now possible to get products both freely and for free, the only reason anyone would pay for your work is if you convince them the trade is worth it. You have to make that happen in a world that may very well come to embrace free distribution.

“Containers do not add to the intrinsic value of water.”

This contradicts your statement about how your labor adds to the value of your work. Thing is, you are also a container. Not a dumb machine, mind you, but you are something that stores and operates on information. In fact, you are a member of the species that built computers, which are tools that seem to reflect our understanding of the world. If your products can exist as information, and your labor makes them more valuable AND you are a container, then yes, containers DO add to the instristic value of the “water”. If you disagree, can you explain why you are not a kind of container?